Lessons Learned on using Chef from Development to Production

Over the past six-months, my team at Alert Logic started and deployed a project where we made heavy use of the Chef infrastructure automation tool. We decided to use Chef from the ground up in our development cycle, from initial coding and testing all the way through final production deployment. Here are some important lessons we learned from the experience.

The Product

For more context in the problem my team was solving, let’s look at the product we developed and its logical deployment architecture.

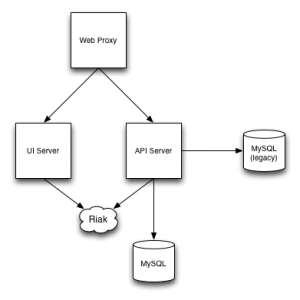

As seen in the following deployment diagram, we have the following key components:

- A web proxy server that efficiently handles SSL termination and directs traffic to either the API or web server.

- A web server that provides our user interface.

- An API and application server, that represents the bulk of the application code.

- A MySQL database server, used for some application data.

- A Riak NoSQL database cluster, used for some application data.

- A legacy MySQL database server that hosts primary customer data.

The Lessons

Chef Roles come from your Logical Deployment

This one is rather obvious: the best roles for your Chef design are those that match the logical deployment components of your application. There is an easy temptation to make roles more fine-grained than they need to be (i.e. not much bigger than a single recipe). Try and avoid this pitfall. Roles best suited us when we thought about the components that always had to belong together. Roles best suited us when they were either a singleton deployment for the application, or something that could easily scale horizontally (stuff in-between these two extremes are more complex and not really a good fit for roles, in my opinion).

If you do it right, then your Chef deployment is simply a matter of assigning roles to various systems. It shouldn’t be any harder than that.

If you do not yet have a good policy for management of SSL certificates and keys you will need to address this upfront.

Chef has a utility to generate SSL certificates within your Chef repo that you can then used to deploy to your servers. This is useful as a development jumpstart mechanism, but is impractical for real production environments or more complex configurations. For example, in our application, we have more than one private Certificate Authority used to generate SSL certificates for internal components.

We settled on a design that had the root certificates, and SSL meta-data, for the Certificate Authorities stored in the Chef repository, and recipes that would generate a new Certificate Authority configuration on a target system from the meta-data stored within the repository. This allowed us to maintain very strict control over the Certificate Authorities (i.e. they were children of other internal Certificate Authorities) while still providing the flexibility we needed for multiple Chef environments.

You may need to rethink how you develop and configuration your applications.

Chef can configure anything, regardless of how much of a mess that anything is. In our application, we had several legacy components that had a plethora of configuration files, each with an set of variables that were largely independent but also shared some commonality.

The most straight-forward way of dealing with this problem in Chef is to create a template for each file, and a definition to prevent the repetition of common variables over and over in Chef recipes. This is great, but made us realize that the design of these configuration components could be improved. Chef was the catalyst for the design change, but the change would result in a cleaner application implementation independent of Chef.

Configuration files work best when there are reasonable defaults provided built-in, and an easy way to override those defaults. Chef works better when you don’t have to replicate an entire configuration file, and try to keep up with versions of that file, and instead focus on providing just the necessary customizations in a deployable template. A poorly designed application configuration file forces you to configure everything all the time, and eliminating that problem in our code provided benefits all around, including a better Chef implementation.

Get your developers on board immediately.

There is a tendency in a lot of organizations (and not just the big ones) that developers never handle any infrastructure issues. How software is deployed in production is a mystery to them and they’d rather someone else handle it. In other organizations, the developers do it all and have difficulty letting go, letting infrastructure duties consume precious time that could be better spent.

Chef allows your developers to both be involved and be disconnected from your infrastructure. If they understand that deploying an infrastructure is really just writing code, then they are more apt to understand what is being done and why. Even if you have an infrastructure specialist creating your Chef deployment infrastructure, your developers can easily follow the code and understand what is going on.

That said, it can be easy for developers to remain ignorant of Chef, and we found this wasn’t ideal. When the entire development team understood how Chef worked and the design of our deployment, we started producing better code that could easily be managed by Chef. We found that the developers quickly began testing better - not only just their code changes, but how their code changes affected the deployment. They also began to appreciate much more the process of moving code from development to test to production. The last was especially important on our team, as we owned the production deployment during the initial beta phases of our application’s lifecycle.

Infrastructure as Code isn’t a Joke

This lesson should be obvious - your Chef deployments are code and need to be engineered as such. Sadly, too often infrastructure is hacked together and not engineered, resulting in a rat’s nest of configuration. Just by using Chef you don’t necessarily solve this issue, but don’t make it worse by hacking together your Chef design.

Stop. Think carefully. Iterate on a design and repeat. Good engineering practices are need - don’t wuss out and cut corners just because it is infrastructure.

Think about when you want to Deploy from Source Code versus Packages

When we did our initial Chef deployment design, we deployed our new software artifacts directly from source control. As the components matured and we had operating system packages ready, we converted our recipes to use packages instead. This seemed like a great idea, as we now had consistent artifacts between development and production and were always testing what we would be deploying in production.

Time proved that this model wasn’t the best for our development cycle. Our team did a lot of integration testing and we found this way of deployment to add a lot of overhead and turn-around time to our day-to-day schedules. We realized that integration testing really wasn’t the same thing as a formal QA test build, which had more in common with a production deployment than an integration test would.

Development versus Production Chef Servers

We used Chef environments to manage the difference between development, test and production deployments. Since an environment lets you have rules for what cookbook versions to use, we could a very easy process for migrating to production was to be very specific about what cookbook versions were in the production environment. Only when our new cookbooks were ready for production did we edit the environment. Several dozen rollouts to production worked perfectly using this technique.

In retrospect, however, we realized this approach alone is not really enough for a real organization. My team could get away with it, but in reality we’d do something different going forward. From our experience, the best approach would be to maintain two or more different Chef servers - one dedicated solely for production. When an application was ready for a production deployment, the various cookbooks and dependencies would then be uploaded to that production server and readied for deployment.

If you are a user of Hosted Chef, likely the best approach is to use two or more separate organizational units within the server. This serves the same purpose, and would keep a nice separation between your engineering and operations departments.

Startups: don’t get lulled into thinking that you can avoid separating engineering and operations just because you are small and nimble. Even in the devops world, this is a best practice and one you will find is mandatory as your company grows. Learn to do it now and don’t cut this corner.

Summary

Chef is an awesome tool. We found it saved us a lot of time in managing our infrastructure, and greatly aided our ability to test our application. When we had to rebuild infrastructure or create a separate test environment it wasn’t a daunting task - it was an easy one.

If you aren’t managing your infrastructure using Chef, or some other infrastructure management tool, you are simply wasting your time. Make your life easier and be a better engineer.